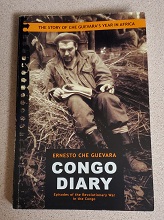

I have been taking advantage of the free time that I now have at my disposal and was reorganizing the book shelves when I came across this book which I had purchased quite some time ago. It is the translated diary of Dr. Ernesto “Che” Guevara (1928-1967), from the failed revoultion in the Democratic Republic of the Congo im 1965. The book was published in 2011 and through the joint efforts of the Che Guevara Studies Center and his widow Aleida March. In the years following the repatriation of Che’s remains to Cuba in 1997, there was a resurgance of interest in his work and this diary is just one of several regarding the revolutions in Cuba, the Congo and Bolivia where he met his untimely death.

I have been taking advantage of the free time that I now have at my disposal and was reorganizing the book shelves when I came across this book which I had purchased quite some time ago. It is the translated diary of Dr. Ernesto “Che” Guevara (1928-1967), from the failed revoultion in the Democratic Republic of the Congo im 1965. The book was published in 2011 and through the joint efforts of the Che Guevara Studies Center and his widow Aleida March. In the years following the repatriation of Che’s remains to Cuba in 1997, there was a resurgance of interest in his work and this diary is just one of several regarding the revolutions in Cuba, the Congo and Bolivia where he met his untimely death.

Che has become a pop culture figure but the reality is that he had no use for captialism and saw American imperialism as a system that needed to be stopped. After great succes in the Cuban revolution, he sought to spread those ideas across Latin America and any nation threatened by imperialism. On June 30, 1960, the Congo achieved independence from Belgium and Patrice Lumumba (1925-1961) became its first prime minister. Less than a year later, he was removed from office, detained and executed in a coup that resulted in the installation of Joseph Kasa Vubu (1915-1969) and Moise Tshombe (1919-1969) to positions of power which they maintained with an iron fist. Guevara had traveled to several African nations as an emissiary of the Cuban Government. And he soon became convinced that a revolution was needed in the Congo to remove the dictators in office and establish true independence.

It is clear early in the journal that Che’s decision to leave Cuba did not come easily and he comments on it right away in this short but revealing passage:

“I was leaving behind nearly 11 years of work alongside Fidel for the Cuban revolution, and a happy home, if that is the right word for the abode of a revolutionary dedicated to his task and a bunch of kids who scarcely knew how much I loved them. The cycle was beginning again.”

I personally could not imagine leaving a wife and five children to take part in a revolutionary struggle thousands of miles away from home. And this part of Che’s life has alwasy left me conflicted. While I always admired his abilty to commit to his beliefs unfailingly, I also questioned whether a father should leave his family for those same beliefs. His widow Aleida has continued to maintain his legacy which is open for debate, depending on the participants in the discussion. She does provide a discussion of her thoughts and feelings regarding their life together in Remembering Che: My Life with Che Guevara.

The tone of the diary is set from the beginning through Che’s words that “this is the story of a failure“. Upon his arrival in the Congo, it becomes clear that there is much work to do if the revolution is to succeed. However, the Congolese and groups of Rwandans who have also joined the resistance movement, are not guerilla fighters and lack the basic tools needed for armed struggle. The Argentine revolutionary kicks into gear and attempts to apply the lessons learned in Cuba to the Congolese struggle but learns over time that the feat is nearly impossible. The discipline and ideological commitment found in Cuba does not exist in the same capacity in the Congo. And the effort is cursed by power hungry and extravagant characters whose only concern is self-endorsement. His anecdotes show the disorganization and monumental challenged he faced in creating a revolutionary army.

Africa is far more diverse than some people realize. Within the borders of the many countries that compose the continent, are hundreds if not thousands of various different langauges and customs. Traditional medicine and superstition are combined in daily life and carried over into the independence movement. The concept of dawa weighs heavily in the story and Che explains its power over the men and the challenge it presented. Throughout the diary, he explains other important aspects of the Congolese culture, in particular food staples that the men are forced to rely on. For Che, the meager and simplistic diet is not a challenge but for the men, it proves to be beyond grueling.

As a trained physican, he notes the medical issues that arise including self-inflcited alcohol poisoning and other ailments including veneral disease. And although he does not take part in much of the fighting himself, he does treat fighters who return from the front lines after having been wounded. He provided descriptions of their conditions and characters in his observations about the reality of their degrading campaign. Hope and optimism had led Che to the Congo but it is not long before see in the diary, a change in his level of confidence in the struggle. In letters between himself, other figures and Fidel Castro (1926-2016) the serious issues developing within the group become critically important and an indicator that doom awaits.

Halfway through the book, it is clear that the Congo revolution is struggling to stay alive. Booze, women and popularity have infected the mindset of a number of fighters. Further, division between the Congolose, Rwandans and Cubans proved to be too much to overcome. Che quickly sums up the issue that had developed:

The Rwandans and the different Congolese tribes regard each other as enemies, and the borders between ethnic groups are clearly defined. This makes it very difficult to carry out political work that aims toward regional union – a phenomenon common throughout the length and breadth of the Congo.

This small passage summarizes the challenges Che faced which he document, in addition to what he believes were his own failures as a leader. Whether he could have truly succeeded is left up to the reader to decide. But what is clear to me is that the mission was doomed from the start and the Congo was not yet ready to be a truly independent nation. Dejected, the Cubans eventually return home to Cuba as well as Che, where he remained until 1967 when he set off for the ill-fated Bolivian campaign from which he would not return alive.

The power that comes with being a dictator has proved to be too seductive for many to resist and Africa has continued to be plauged by megalomaniacs who have failed to bring economic wealth and true democracy. Poverty, sham elections and crackdowns against resistance to government policy continues to this day. Perhaps the polticial and social climate in many parts of Africa will one day change and they do, it will have to be through diplomacy and not armed struggle. And if we need a reminder of why violence will not succeed, Che’s words here are perfect reference guide.

ISBN-10: 0980429293

ISBN-13: 978-0980429299

The lone gunman theory remains the official position taken the United States Government with regards to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy (1917-1963). The alleged assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald (1939-1963) was convicted in the court of public opinion before standing trial in a Dallas courtroom. His assailant, Jack Ruby (1911-1967) permanently silenced Oswald forever and prevented Americans from knowing more about the former Marine that had once lived in the Soviet Union. The big question surrounding Kennedy’s death is who did it? The crime is similar to a black hole, puzzling even the most hardened researchers. The late Jim Marrs (1943-2017) once said that we know who killed Kennedy, we just have to look at the evidence. Author John M. Newman has joined the group of assassination researchers and has produced this first volume in what will be a multi-volume set about the deadly events in Dallas, Texas on November 22, 1963.

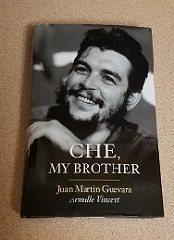

The lone gunman theory remains the official position taken the United States Government with regards to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy (1917-1963). The alleged assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald (1939-1963) was convicted in the court of public opinion before standing trial in a Dallas courtroom. His assailant, Jack Ruby (1911-1967) permanently silenced Oswald forever and prevented Americans from knowing more about the former Marine that had once lived in the Soviet Union. The big question surrounding Kennedy’s death is who did it? The crime is similar to a black hole, puzzling even the most hardened researchers. The late Jim Marrs (1943-2017) once said that we know who killed Kennedy, we just have to look at the evidence. Author John M. Newman has joined the group of assassination researchers and has produced this first volume in what will be a multi-volume set about the deadly events in Dallas, Texas on November 22, 1963. October 10, 1967 – Argentine newspaper Clarin announces that Ernesto “Che” Guevara (1928-1967) has died in Bolivia on October 9 after being capture with a group of guerrilla fighters attempting to spread revolutionary ideology throughout Latin America. In Buenos Aires, his family receives the news of his death and is completely devastated. Juan Martin, his younger brother, races to his father’s apartment where his mother and siblings have gathered as they attempt to piece together the last moments of Ernesto’s life. Che was secretly buried in an unmarked grave and his remains remained hidden for thirty years before author Jon Lee Anderson convinced a retired Bolivian general to reveal the grave’s location. His remains were returned to Havana on July 13, 1997 where he was buried with full military honors on October 17, 1997. In death, Che’s legacy grew exponentially and even today in 2017, he is the icon of revolution around the world. But after his death, what happened to his family and where did their lives take them? Juan Martin, at seventy-two years old, has decided to tell his story and reveal to us many facts about the Guevara family that have sometimes been overlooked by history.

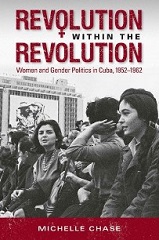

October 10, 1967 – Argentine newspaper Clarin announces that Ernesto “Che” Guevara (1928-1967) has died in Bolivia on October 9 after being capture with a group of guerrilla fighters attempting to spread revolutionary ideology throughout Latin America. In Buenos Aires, his family receives the news of his death and is completely devastated. Juan Martin, his younger brother, races to his father’s apartment where his mother and siblings have gathered as they attempt to piece together the last moments of Ernesto’s life. Che was secretly buried in an unmarked grave and his remains remained hidden for thirty years before author Jon Lee Anderson convinced a retired Bolivian general to reveal the grave’s location. His remains were returned to Havana on July 13, 1997 where he was buried with full military honors on October 17, 1997. In death, Che’s legacy grew exponentially and even today in 2017, he is the icon of revolution around the world. But after his death, what happened to his family and where did their lives take them? Juan Martin, at seventy-two years old, has decided to tell his story and reveal to us many facts about the Guevara family that have sometimes been overlooked by history. The Cuban Revolution has served as a blueprint as a successful campaign for independence from imperialism. Fidel Castro (1926-2016), Ernesto Che Guevara (1928-1967) and Raul Castro (1931-) became legendary figures in Cuba and around the world. Raul is remaining member of the trio and is currently the President of the Council of State of Cuba and the President of the Council of Ministers of Cuba following Fidel’s retirement in 2008. In March, 2016, United States President Barack Obama made a historic visit to the island in an effort to restore severely strained diplomatic relations between the two nations. Time will tell if Washington and Havana continue down that path.

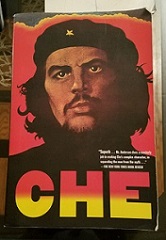

The Cuban Revolution has served as a blueprint as a successful campaign for independence from imperialism. Fidel Castro (1926-2016), Ernesto Che Guevara (1928-1967) and Raul Castro (1931-) became legendary figures in Cuba and around the world. Raul is remaining member of the trio and is currently the President of the Council of State of Cuba and the President of the Council of Ministers of Cuba following Fidel’s retirement in 2008. In March, 2016, United States President Barack Obama made a historic visit to the island in an effort to restore severely strained diplomatic relations between the two nations. Time will tell if Washington and Havana continue down that path. October 8, 2017 will mark 50 years since Ernesto “Che” Guevara died in the jungles of Bolivia as he attempted to spread revolutionary ideology throughout Latin America. The legendary and iconic symbol for revolution around the world became a martyr in the process and to this day, his image can be found on posters, hats, shirts and even coffee mugs. His final campaign to bring revolution to Bolivia and the tragic fate that awaited him is one of the defining stories of the 20th century. Guevara, the razor-sharp Argentine intellectual, posed a threat to the dominance of imperialism throughout Latin America and in particular was a deadly threat to the business interests of United States businessmen. His death brings a sigh of relief to many governments around the world and deals a devastating blow the Castro regime in Cuba. Che, although no longer legally a citizen of Cuba at that point, is finally returned home 30 years after his death, when he is returned with several other revolutionaries in 1997 and buried in Santa Clara.

October 8, 2017 will mark 50 years since Ernesto “Che” Guevara died in the jungles of Bolivia as he attempted to spread revolutionary ideology throughout Latin America. The legendary and iconic symbol for revolution around the world became a martyr in the process and to this day, his image can be found on posters, hats, shirts and even coffee mugs. His final campaign to bring revolution to Bolivia and the tragic fate that awaited him is one of the defining stories of the 20th century. Guevara, the razor-sharp Argentine intellectual, posed a threat to the dominance of imperialism throughout Latin America and in particular was a deadly threat to the business interests of United States businessmen. His death brings a sigh of relief to many governments around the world and deals a devastating blow the Castro regime in Cuba. Che, although no longer legally a citizen of Cuba at that point, is finally returned home 30 years after his death, when he is returned with several other revolutionaries in 1997 and buried in Santa Clara.

You must be logged in to post a comment.